Frank Ryan: A revolutionary life

Who was Frank Ryan? Why does he remain such a compelling figure in Irish history? Does he deserve his reputation as one of the leading figures of the Irish republican left or has his legacy been compromised by his links with Nazi Germany? Ryan's biographer, Fearghal McGarry, considers the evidence.

One of the most intriguing aspects of Frank Ryan’s extraordinary life is his prominent place in Irish history. Despite dying in controversial circumstances in Nazi Germany, he remains one of the most widely admired figures in Irish republican history. Although he didn’t play a significant role in the Irish revolution, or exercise political power, or leave behind a body of political writing to influence subsequent revolutionaries, he remains among the best-known republicans of the last century. He has been the subject of biographies, television documentaries, ballads, novels, academic debate and now a major historical film by Des Bell. Why does Ryan continue to hold such a grip on the public imagination?.

Early life and republican activism

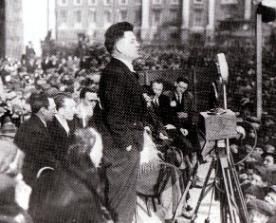

Caption Test

There was little about Frank Ryan’s early life to mark him out for attention. Born near Knocklong, Co. Limerick, on 11 September 1902, he was the seventh of nine children of national-school teachers Vere Francis Ryan and Anne Slattery. After completing his secondary education at St Colman’s College, Fermoy, he joined the IRA’s East Limerick brigade shortly before the truce of July 1921. An opponent of the Treaty, Ryan spent most of the Civil War interned in the Curragh following his capture by Free State troops. It was while in prison, where he edited an Irish-language camp journal, that his skills as a propagandist became evident. After his release, he completed a degree in Celtic studies at University College Dublin, where he edited the Irish language society’s journal and earned a gold medal for oratory (an ability that would serve him well throughout life).

Failing to establish a career as a school teacher, Ryan became a prominent figure in the anti-treaty IRA in 1920s Dublin. Following defeat in the Civil War, the IRA was a demoralised and directionless force: suppressed by the Free State authorities, it also found itself marginalised by Eamon de Valera’s new political party, Fianna Fail, which led anti-treaty republicanism in a non-violent direction.

During these years Ryan’s imposing physique, charisma, and powerful – if reckless – rhetoric marked him out as a natural leader at political demonstrations (and the street-fighting that often accompanied them). His skills as a propagandist led to his appointment as editor of the IRA’s newspaper, An Phoblacht, in 1929. By now, Ryan had become an important figure in the IRA: he was appointed adjutant of its Dublin Brigade in 1926, and was elected to the IRA’s ruling executive in 1929.

Ryan was a passionate, brave and idealistic figure, but he was also intolerant, strident and militaristic in his outlook. He was a source of inspiration for his revolutionary comrades, but a hate figure for the Free State’s Special Branch which bore the brunt of IRA violence. Popular and likeable, he was well-known and widely admired within Dublin’s close-knit Irish-speaking and republican circles. He was a particularly attractive figure for women: he was engaged to Bobbie Walsh for a period and had numerous romances, including a lengthy, but clandestine, relationship with the novelist and activist Rosamond Jacob

Ryan was a passionate, brave and idealistic figure, but he was also intolerant, strident and militaristic in his outlook. He was a source of inspiration for his revolutionary comrades, but a hate figure for the Free State’s Special Branch which bore the brunt of IRA violence. Popular and likeable, he was well-known and widely admired within Dublin’s close-knit Irish-speaking and republican circles. He was a particularly attractive figure for women: he was engaged to Bobbie Walsh for a period and had numerous romances, including a lengthy, but clandestine, relationship with the novelist and activist Rosamond Jacob

Anti-fascism and the Spanish Civil War

In the late 1920s Ryan’s political outlook began to develop in a left-wing direction, reflecting a wider shift within the IRA. He was influenced by his friend and comrade, Peadar O’Donnell, who stressed the need for economic – as well as political – revolution to achieve a united Irish republic. In 1931 he was a supporter of Saor Eire, a left-wing republican initiative, which collapsed against a background of government repression, clerical-inspired anti-communism, and indifference from the IRA leadership. In January 1932 he was jailed for contempt and sentenced to three months in Arbour Hill prison, where he went on hunger strike after refusing to wear prison clothes. He was released by the new Fianna Fail government following the general election of 1932 as part of its efforts to conciliate the IRA.

The early 1930s was a tumultuous period in Irish and European politics. Fianna Fail’s election demonstrated growing public support for republicanism but at the same time called into question the need for a private republican army. 1930s Ireland was also shaped by international forces. The IRA’s shift to the left was partly a response to the Great Depression which polarised society between left and right across Europe. The rise of fascism as a powerful international force was echoed, in an ideologically incoherent way, by the emergence of Eoin O’Duffy’s pro-treaty Blueshirt movement. The street-fighting that characterised Irish politics in 1933 and 1934 reflected international as well as Irish forces, and Ryan would play a prominent role in opposing what he saw as the fascist threat at home and abroad.

After a split between left-wing republicans and the IRA leadership (which regarded conflict with the Blueshirts as a distraction and opposed the socialist direction advocated by left-wing republicans), Ryan and a substantial minority of republicans formed Republican Congress in April 1934. Congress aimed to unite the working classes (north and south), small farmers and other radicals in a left republican alliance. It soon split, however, as a result of tensions between its nationalist and socialist objectives, a tension which remained a defining feature of Ryan’s political career.

In July 1936 the Spanish Civil War, an event that would transform Ryan’s life, began when General Franco – backed by other right-wing army generals, landowners and the Spanish Catholic Church – attempted to overthrow the democratically-elected Republican government. In December, Ryan led the first contingent of a force of over two hundred Irishmen to fight in the International Brigades. Why did Ryan commit himself to Spain? He may have been influenced by the lack of a viable political role in Ireland. Republican Congress had collapsed, he was unemployed, and the IRA no longer held any appeal for him.  Having played a leading role in organising Irish support for the Popular Front government since the summer of 1936, he may have felt personally obliged to fight alongside those Irishmen who were already volunteering for Spain. He also felt the need to oppose the Irish fascist leader, Eoin O’Duffy, who was bringing a much larger Irish force to fight for Franco. Internationalism also played a role: like other radicals throughout Europe and the wider world, Ryan was drawn to Spain because it was the frontline in the fight against fascism.

Having played a leading role in organising Irish support for the Popular Front government since the summer of 1936, he may have felt personally obliged to fight alongside those Irishmen who were already volunteering for Spain. He also felt the need to oppose the Irish fascist leader, Eoin O’Duffy, who was bringing a much larger Irish force to fight for Franco. Internationalism also played a role: like other radicals throughout Europe and the wider world, Ryan was drawn to Spain because it was the frontline in the fight against fascism.

Although he never held a field command position, Ryan played an important role within the International Brigades. Promoted to major, he was the most senior Irish officer in the International Brigades and acted as de facto leader of the Irish in Spain (smoothing tensions between the Irish volunteers and their English comrades within the British battalion, and liaising between the sometimes unruly Irish and the communist-led International Brigade leadership). Although primarily involved in political work – he wrote and broadcast propaganda from Madrid – he was injured in the battle of Jarama in February 1937. It was at Jarama (for all his militarism – one of the few occasions Ryan was ever tested in battle) that he demonstrated real courage, playing a pivotal role in shoring up the collapsing morale of British battalion which had been decimated by the onslaught of superior military forces.

Collaboration

After a short sojourn in Ireland, recovering from wounds received at Jarama, Ryan returned to Spain where he was captured by Italian troops at Calaceite, near Gandesa, on the Aragon front in March 1938. Thus began the final – and strangest – chapter in Ryan’s career. For reasons that remain unclear – and despite diplomatic and political pressure from Ireland, Britain and the United States – Ryan remained incarcerated at San Pedro de Cardena prison long after the end of the Spanish Civil War and the release of other international prisoners. While a prisoner of Franco, Ryan demonstrated great personal courage in his dealings with the prison authorities, refusing to give the fascist salute and agitating against the conditions there.

Ryan’s freedom was finally secured in July 1940 by Admiral Canaris, head of German military intelligence (Abwehr), who engineered Ryan’s ‘escape’ in order to strength German links with the IRA. Ryan’s release was aided by the Irish minister in Spain, Leopold Kerney, and the efforts of two Abwehr agents – Jupp Hoven and Helmut Clissmann (husband of Elizabeth Mulcahy, a mutual friend of Ryan and Kerney). Ryan – increasingly deaf and in poor health – was brought to Berlin where he was reunited with Sean Russell, the IRA’s chief of staff, who was about to return to Ireland to use German support to foment anti-British agitation. Russell, however, died on a German submarine off the Irish coast, and Ryan – despite his anti-fascist record – agreed to return to Berlin to replace Russell as a liaison between Irish republicans and Nazi Germany.

Although his motives remain the subject of much controversy, it seems likely that his decision to return to Berlin was based on the assumption that, should Germany invade Britain (or Britain pre-emptively seize the Treaty ports), he would play an important role liaising between Irish republicans and Germany in the subsequent conflict that would follow. Ryan, like many Irish republicans, believed that the war offered a historic opportunity to reunify Ireland. However, Germany’s failure to invade Britain, and the opening of a second front against the Soviet Union, saw Ryan become an increasingly irrelevant figure. Although sometimes depicted as a captive of Nazi Germany, Ryan – protected by his status as an Abwehr agent under the personal protection of the powerful and ruthless Nazi Dr Edmund Veesenmayer – was well-treated; in return he provided political advice on Irish affairs and resisted attempts to draw him into closer collaboration with the regime. Despite his ailing health, de Valera refused to allow Ryan to return to Ireland on the basis that it would threaten Irish neutrality. In January 1943, Ryan suffered a stroke: he died in Loschwitz Sanatorium, near Dresden, on 10 June 1944.

Legacy

Why did Ryan’s links with the Nazi regime not discredit his reputation? The astonishing revelation that Ryan, Ireland’s most celebrated anti-fascist, had spent the war in Berlin did cause concern in republican circles: in 1945 a commemoration committee decided not to publish the biography they had commissioned after his death in anticipation of revelations of collaboration. However, precise information about his activities in Germany did not emerge, and few seemed inclined to examine his activities there too deeply. By the 1970s the political context had changed. The popular Irish perception of the Spanish Civil War had shifted from that of a communist war against Catholicism to a conflict between progressive democratic values and fascism. As the leader of the Irish in Spain, Ryan came to personify these values. A certain tragic glamour was attached to his early death, transforming him into a progressive symbol of anti-fascism whose useful legacy was claimed by republican organisations across the political spectrum.

Why did Ryan’s links with the Nazi regime not discredit his reputation? The astonishing revelation that Ryan, Ireland’s most celebrated anti-fascist, had spent the war in Berlin did cause concern in republican circles: in 1945 a commemoration committee decided not to publish the biography they had commissioned after his death in anticipation of revelations of collaboration. However, precise information about his activities in Germany did not emerge, and few seemed inclined to examine his activities there too deeply. By the 1970s the political context had changed. The popular Irish perception of the Spanish Civil War had shifted from that of a communist war against Catholicism to a conflict between progressive democratic values and fascism. As the leader of the Irish in Spain, Ryan came to personify these values. A certain tragic glamour was attached to his early death, transforming him into a progressive symbol of anti-fascism whose useful legacy was claimed by republican organisations across the political spectrum.

In 1979 Ryan’s body was exhumed, in a ceremony conducted with full military honours, from its place of burial in communist-East Germany and reinterred in the Republican Plot in Glasnevin. His burial was attended by leaders from every shade of Irish republicanism, and described by the Irish Times as ‘an event of historic importance’. In 1980 an influential biography of Frank Ryan, written by former IRA chief of staff Sean Cronin, exonerated Ryan from the charge of collaboration: ‘He worked for no one. He was his own master’. This view of Ryan as a victim of circumstances – or even a prisoner of Nazi Germany – came to be widely accepted by Irish republicans for whom the IRA’s collaboration with Nazi Germany remains a chapter of history best forgotten.

In 1979 Ryan’s body was exhumed, in a ceremony conducted with full military honours, from its place of burial in communist-East Germany and reinterred in the Republican Plot in Glasnevin. His burial was attended by leaders from every shade of Irish republicanism, and described by the Irish Times as ‘an event of historic importance’. In 1980 an influential biography of Frank Ryan, written by former IRA chief of staff Sean Cronin, exonerated Ryan from the charge of collaboration: ‘He worked for no one. He was his own master’. This view of Ryan as a victim of circumstances – or even a prisoner of Nazi Germany – came to be widely accepted by Irish republicans for whom the IRA’s collaboration with Nazi Germany remains a chapter of history best forgotten.